WWPH Writes: Issue # 18

Dedicated to Poetry & Fiction Writers in the DMV

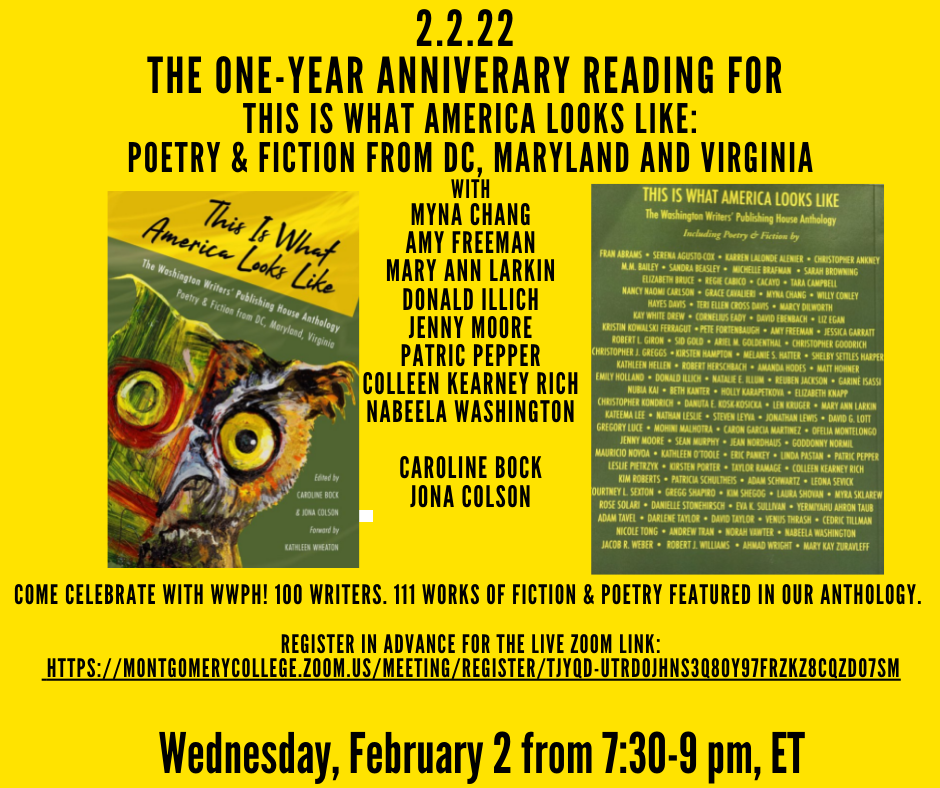

You are invited! Join us this Wednesday, February 2nd from 7:30-9 pm, ET to celebrate the first anniversary of THIS IS WHAT AMERICA LOOKS LIKE: Poetry & Fiction from DC, Maryland, and Virginia. Register for the Zoom Link here. We are featuring fiction writers and poets from the anthology, many of who are reading for the first time–and both of us will be joining the reading/celebration as well. Let’s toast together the anniversary of the WWPH anthology that features 100 writers and 111 works, an anthology that dives deep into the questions of what America looks like with the pandemic, with social justice reckonings, and with our fears and hopes. Join us! More details at the end.

But first, read “Snow Days,” the evocative prose poem by Ariel M. Goldenthal, especially perfect for this winter weekend, and The Café on Dream Street, the equally evocative novel excerpt from Adriane Brown. Reminder: we are currently reading for our late spring editions; submit to us your poetry and short fiction/novel excerpt. After only six months of publication, we are approaching 1,000 subscribers for WWPH Writes, and we want to see your work in our DMV literary journal.

We hope to see you on 2.2.22!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

Co-editors, WWPH Writes

WWPH Writes: Poetry

Ariel M. Goldenthal is an Assistant Professor of English at George Mason University. Her work has appeared in Tiny Molecules, Emerge Literary Journal, MoonPark Review, the WWPH anthology This is What America Looks Like, and others.

Snow Days

The ice might melt one day, my father said. Fleece-lined jacket flush across my flesh, bright pink against the freshly fallen snow. Mother’s face ripples through the window’s glass. She won’t come out below. Footprints tracked along the flakes, a heart in recess. I pull Talya close, feel her black fur and clumps of our time outside enmeshed. Don’t drip drop on the kitchen floor, he said. Mother will be angry, I know. The ice might melt one day, my father said.

We drag snow-dusted ice blocks from between the maple trees and build an igloo big enough for two, we guess. You ask why mother can’t make us hot chocolate and though I know, I want to keep you un-shadowed. In April dad collects us from school just before the buses freeze in the spring blizzard. Safety warnings on the radio. Mother screams we belong with her. I can’t drive in this weather I hear my father say. Silence. Progress. The ice might melt one day, my father said.

© Ariel M. Goldenthal 2022

WWPH Writes: Fiction

Award-winning author, Adriane Brown, received first prize in the Maryland Writers’ Association 2021 novel competition in the mainstream/literary fiction category. She is a long-time political activist and teacher who taught for many years in both the California and the Montgomery County, Maryland public schools. As a public school teacher, she personally witnessed the heartbreak that occurs when a family member is deported and the palpable fear with which immigrant families live daily. Her experiences became the basis for her debut novel, The Café on Dream Street, a novel that focuses on the social and political dynamics of immigration and the communities in which immigrants live.

Green with tropical forests and crimson with blood, hot with the fire of volcanoes and the relentless sun that beats down on coffee pickers, cold with death. When the rains come down, it is not really rain at all but the tears of a grieving people that soak the land and make the coffee grow.

Felipe rose with a sense of foreboding, just couldn’t shake the feeling that something bad was going to happen. Mama roused him at dawn most days, but today she didn’t have to coax him at all because he had been awake most of the night.

The morning sunlight filtered through the leafy green branches of the laurel trees as he carried the pear-shaped dried gourd, the tecomate, to the river, where he would fill it with water for Mama, who was preparing their breakfast of tortillas, beans, and salt. He was already too warm in his thin white shirt, so he threw it off and tossed it by the bank of the Rio Escondido, next to the tecomate. The river was still chilly from the night air, but his body warmed to it quickly as he plunged in and floated on his back for a few precious minutes. The river water lapped gently against his skin, soothing him as he floated, gazing up at the glorious blue sky of early morning, listening to the birds warbling to each other as they scouted for breakfast while the sun came up.

High above him, a green parrot squatted on a branch blinking one black eye, maybe the same parrot he had seen a few days ago in a tree by the choza, the one room hut he shared with his parents and his sister and brother. Such a beautiful parrot deserved a name, so he made one up on the spot. Verdito, little green one, he would call him. “Hola, Verdito,” he called to the parrot. There were no clouds in the sky today, and he wondered where the clouds went when they weren’t in the sky.

Papa had been coughing all night, a rumbling, hacking cough that awakened Juanito, the baby, who was frightened by the noise. Mama sat on a straw mat, rocking him, singing a lullaby. “Vaya cierre sus ojitos, close your little eyes, canasunganana, canasunganana,” she had cooed, but Juanito continued crying and Papa continued coughing, so no one got much sleep.

The sun was higher now, its bright yellow face reminding Felipe that it was time to go to the finca, the coffee plantation, to begin the day’s work. He slid the tecomate into the river, holding it steady, the water gurgling softly as it rose to the top. His shorts were cool against his skin from the river water, taking the edge off the heat that was already baking the dirt under his feet and drying the dampness in his hair.

The scent of smoke wafted through the air and Mama appeared in front of the choza, her black hair tied into a bun, her slender body bent over the hornilla cooking tortillas. The choza, a one room hut built of wood, had a thatched roof covered with dried grass and only a tiny window to allow in natural light, but this morning a streak of sun streamed across the dirt floor, dancing on the straw sleeping mats and Papa’s sombrero that sat in the corner.

The mats were usually rolled up and hung from the wall during the day, but today Papa was still lying there long after the sun rose. Felipe placed the tecomate in the corner next to a small bag of corn meal, two machetes, and Papa’s sombrero, then sat down on the floor next to Papa. Papa clutched the sides of the mat and attempted to push himself to a sitting position.

“Papa,” Felipe said quietly. “Papa, maybe you shouldn’t go to the finca today.”

“I don’t get paid if I don’t work, mijo, and they were not happy about the sick days I took last week. If I don’t go in today, they’ll fire me for sure—then what will I do?”

“I’ll work extra hours until you feel better, Papa. I can do any job there, even loading trucks,” Felipe answered, pleading with him now.

Juanito had finally fallen asleep, wrapped in a blanket, breathing rhythmically on the straw mat. Mama put her arm around Felipe, squeezing his shoulder. “I’m very proud of you for wanting to help, Felipito, but nine hours a day is plenty for a thirteen-year-old. Papa will manage.”

Felipe and Papa trudged down the long stretch of road that led to the finca, a trip that usually took them an hour if they moved along at a brisk pace. Today they had gotten a late start and needed to hurry, but Papa kept stopping every few minutes to catch his breath, and they couldn’t seem to propel themselves faster than the armadillo that poked sluggishly across the road in front of them.

More than an hour had passed before the multi-hued shirts of the coffee pickers appeared in the distance, splotches of color peeking through the green leaves of the coffee bushes. Gauzy white tropical shirts, plaid sport shirts with buttons opened to the waist, some white T-shirts, some brightly colored ones.

Felipe’s friend Ernesto and his father, Oscar, were pulling coffee beans from the plants and putting them into baskets strapped around their waist, while other families washed them and spread them out to dry on stone terraces called drying platforms. Men with muscled brown arms and faces damp with sweat peered out from under their straw hats, as they loaded the jute sacks filled with coffee beans onto trucks. The beans were transported to a beneficio, where they were processed—small separated from large, red from yellow from green—then washed to take off all the debris and loaded into a machine to remove the pulp.

As they entered the finca, the freshness of the earth in the early morning and the sweet smell of coffee beans mingled with another odor—the acrid smell of gunpowder.

© Adriane Brown 2022

WWPH Community News

WWPH Writes is the bi-weekly literary journal of The Washington Writers’ Publishing House, a nonprofit, 501c3, all-volunteer, cooperative press launched in 1975 by a group of DC area poets. You can now easily donate to WWPH and help us support and celebrate DMV writers via our new donation page. Interested in doing more? We are also looking for a sponsor to ‘name’ our annual Fiction Award (a multi-year but relatively modest commitment). Please email us at wwphpress @ gmail.com if you are interested in this once-in-a-lifetime gift!

Thinking of submitting to WWPH Writes? We are looking for poetry and fiction that celebrate, unsettle, and question our lives in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia area (DMV) and our nation. We seek work that is lyrical and dynamic, and we believe in cultivating a diverse and inclusive environment of content, form, risk, and experimentation. New perspectives and voices with craft and fierceness are strongly encouraged to submit. It’s FREE to submit, but you must live in the DMV. Please send us your best work–challenge us with your ideas and writing. We look forward to reading your poems and stories in 2022! Submit here.

Looking forward to seeing you on 2.2.22 for our First Anniversary Reading! Register for ZOOM LINK here.

Caroline Bock

Fiction Editor, WWPH Writes

Jona Colson

Poetry Editor, WWPH Writes