Welcome to WWPH Writes 50! We are so grateful to have made it to 50 issues, and we look forward to 50 more! In Wedding Poem, Danielle Badra, the current poet laureate of Fairfax County, celebrates vows on a wedding day—a beautifully crafted poem that bears witness to love and commitment. Kathleen Wheaton’s Redwood delves into generational, family bonds and ends with the haunting line “Mackie, tall and thin as a redwood sapling, would give the bride away.” Ties. Family. Love. We are dedicated to building an inclusive literary community here at WWPH Writes and at the Washington Writers’ Publishing House, and on June 1st, we will launch our first annual WWPH PRIDE Poetry & Micro Prose contest. Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-editors, WWPH Writes

WWPH WRITES: POETRY

Danielle Badra received her BA in Creative Writing from Kalamazoo College (2008) and her MFA in Poetry from George Mason University (2017). Her poems have appeared in Mizna, Guesthouse, Cincinnati Review, Duende, The Greensboro Review, Bad Pony, Rabbit Catastrophe Press, Split This Rock, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, and elsewhere. Dialogue with the Dead (Finishing Line Press, 2015) is her first chapbook, a collection of contrapuntal poems in dialogue with her deceased sister. Her manuscript, Like We Still Speak, was selected by Fady Joudah and Hayan Charara as the winner of the 2021 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize and published through the University of Arkansas Press fall of 2021. She is the current Fairfax County Poet Laureate.

WEDDING POEM

-for Holly

My world, each day we dance into nightfall.

My gladness, we offer arms and autumn.

At night, we are illuminated lovers receiving courage.

My dear, our love is enduring and triumphant.

Nothing is as freeing as your eyes as stars look surrendered to light.

Your nature to grow art into lavender honey could coat our home in devotion.

The moon is a dancer at this festival of love.

*The final italicized line is a Rumi quote. This poem was part of my wedding vows.

©Danielle Badra 2023

WWPH WRITES: FICTION

Kathleen Wheaton is the author of Aliens and Other Stories, which received the Washington Writers’ Publishing House Fiction Prize in 2013. She then served as president of WWPH from 2014 to 2022. Her stories have appeared in many journals and she is a six-time recipient of Maryland State Arts Council grants. Redwood is from her forthcoming collection, A History of the Modern World.

REDWOOD

Mackie was responsible for his mother’s death. Nobody blamed him—he had to get born! How did a baby come out of its mother’s body? Through a special door. This he learned from his nurse, Molly. It was 1918 in Oakland, California. Mackie was four. He lived in a redwood-shingled house with tall windows, along with his twelve-year-old brother, Henry, his eleven-year-old sister, Isobel, and their distracted, grieving father. The garden overlooked an arroyo and was fragrant with lantana, jasmine, roses.

Clara, a friend of their father’s, had found Molly. Back in Ireland, Molly had lived in a castle, where she took care of two silky-haired English girls who never spilled their tea.

On her first afternoon in Oakland, Molly made a pot of tea and carried it upstairs to the nursery on a tray with four cups. Mackie wanted tea, with milk and lots of sugar. Isobel, reading in the window seat, said ‘No’ without looking up.

Molly didn’t scold her. After a while Isobel said, ‘No, thank you.’ Molly nodded.

‘Oh, all right,’ Isobel said, and flung her book down. In her stocking feet she padded down the hallway to fetch Henry, who was in his room with his king snake and the mice he raised to feed it and his pet raccoon in a cage. Henry came along but stood in the doorway, refused the tea.

‘I killed our mother,’ Mackie said, to start the conversation.

‘Why, Mackie, you didn’t mean to!’ Isobel exclaimed.

‘Maybe he did,’ Henry said. He was smiling, which meant he was kidding.

Molly would answer any question you asked. What was Ireland like? Lovely, soft green. Not like California, so brown it made her thirsty to look out the window. What happened to the English girls? Republicans set fire to the castle, so the family had to return to England, leaving Molly lonely as a unicorn.

The three children, also Republicans, glanced uneasily at one another. “Houses made of redwood don’t burn,” Henry said.

Molly said the color of the house didn’t matter. She said that in Irish, unicorn and lonely are the same word. That the boat to America was full of ruffians. That she didn’t care for men, particularly.

‘Me neither,’ said Isobel, who over her long life would marry four times.

One night, having his bath, Molly explained to Mackie how babies came out of mothers. He pictured a small, round door, like the door to Peter Rabbit’s burrow.

Mackie could read. Nobody had taught him. As she’d done with the English girls, Molly read him The Tale of Peter Rabbit before he went to sleep at night. Then suddenly he could do it alone—it was like being pushed in a swing.

‘You’ve just memorized it,’ Henry said. But no, Mackie could pick out words in other books, even in the newspaper.

In the fall, the whole household had Spanish ‘flu. After they were better, Clara came with flowers and a custard. Mackie read Peter Rabbit to her. ‘Oh, my stars,’ Clara said, and hugged Mackie sideways. Her dress rustled like dry grass.

‘He’s a prodigy,’ said Mackie’s father, who was an architect. He sat across the room with an afghan over his long legs, whiskey in a heavy glass.

‘There’s your special door, Clara.’ Mackie pointed to the picture in the book.

‘My door?’ Clara said.

‘For a baby to come out. All ladies have them. Molly told me.’

‘Oh, dear,’ Clara laughed. ‘I am sorry, Roger. She came highly recommended.’

His father shrugged. ‘She’s a country lass. I’m glad you see the funny side.’

‘I’ll find you the right person to raise the children, I promise. I’m so fond of you, Roger. I’m fond of all of you.’

‘I know,’ his father said. He looked into his glittering glass. ‘Thank you.’

A month later, he was dead, too, of a golfing wound. It said so in the newspaper. Later Mackie heard someone say that his father had been cleaning his gun. Cleaning it on the golf course? Henry had a .22 rifle which he cleaned on the floor of his room, after putting down newspapers to protect the carpet. The shells were kept in a box on top of the bureau. Their father had said that if he ever walked in and saw the gun and the bullets stored together, Henry would receive a walloping he’d never forget.

You’d think that Mackie, the prodigy, would never forget the funeral of his own father. Five hundred people attended. For the rest of his life, Mackie would sift through his memories, but it was gone. What he remembered was the last morning in Oakland before they took the ferry to San Francisco, where they were to live with their great-uncle: Molly counting suitcases, securing her hat under her chin with a shoelace for the windy voyage across the bay. Twenty years hence, at age eighty, this uncle would marry his nurse. Mackie, tall and thin as a redwood sapling, would give the bride away.

©Kathleen Wheaton 2023

WWPH Community News

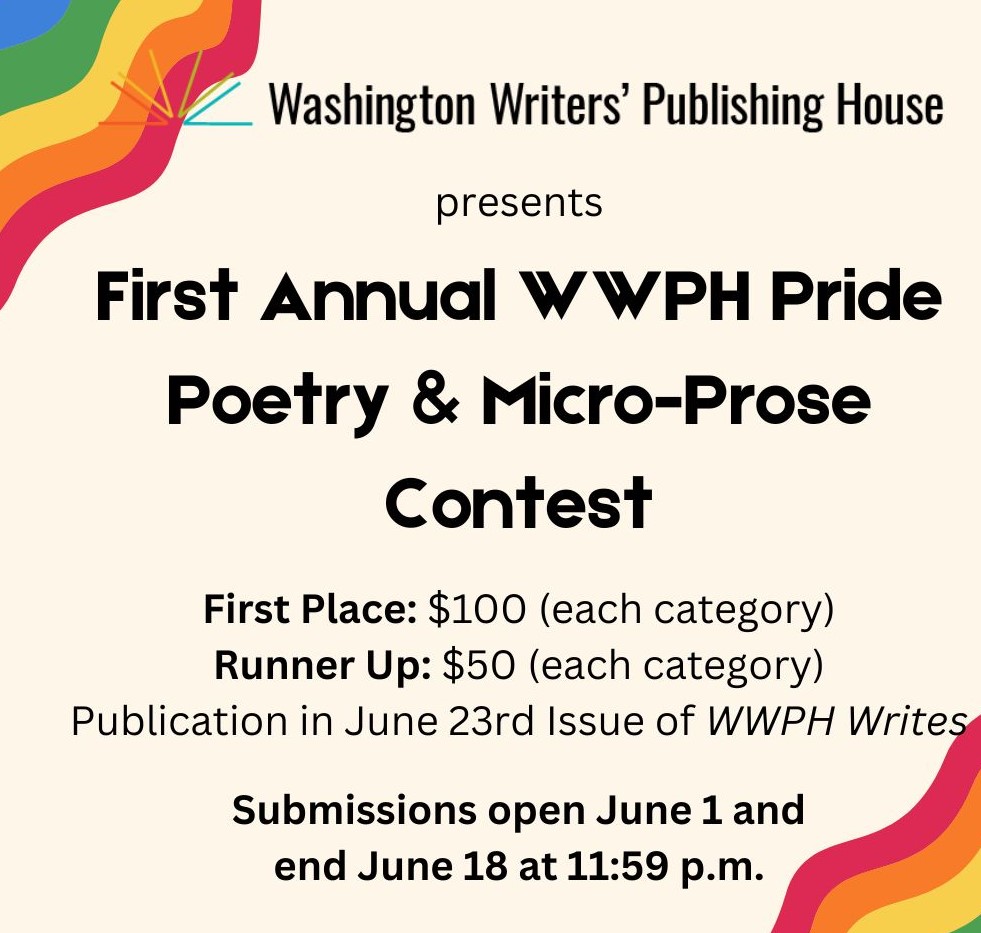

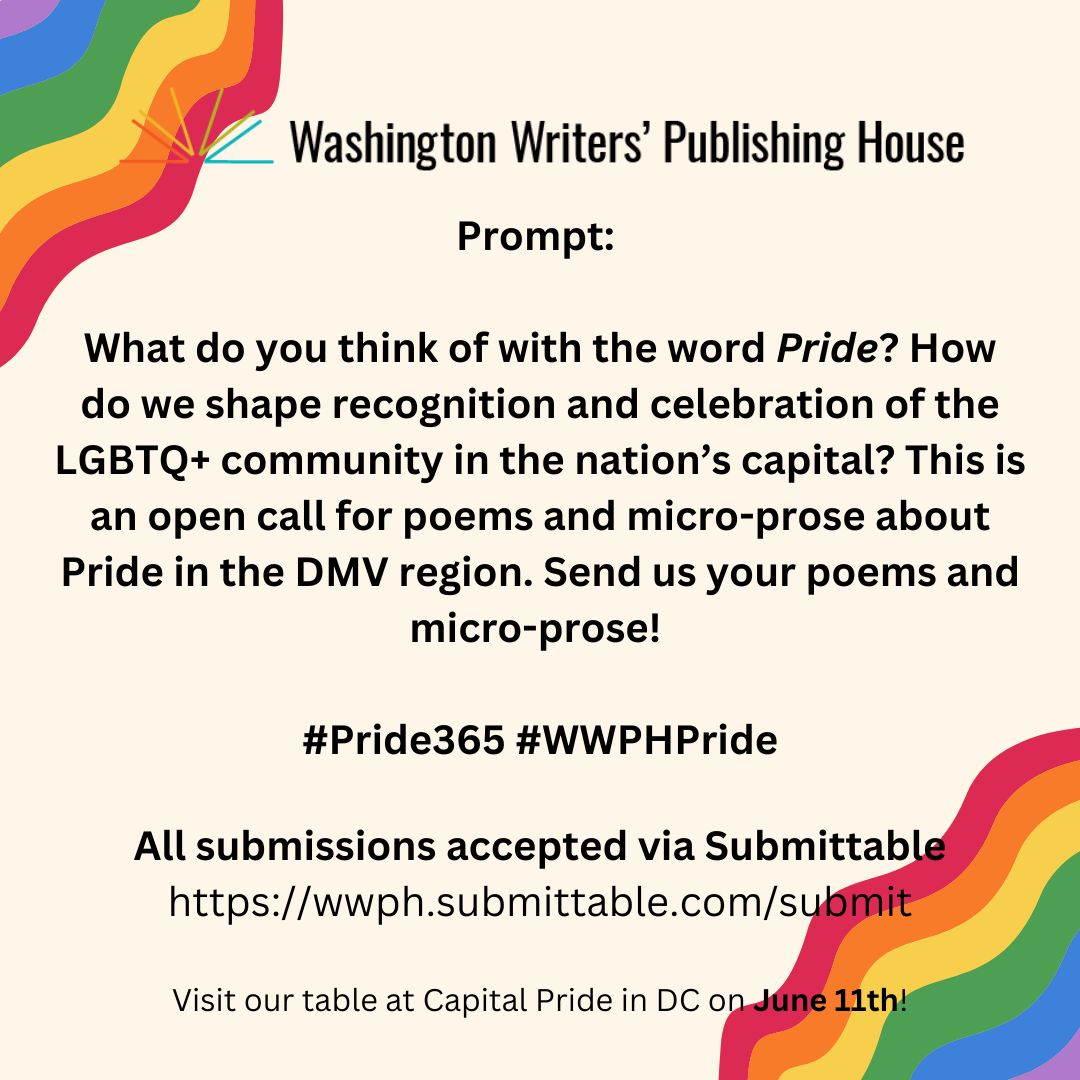

Come visit us at the Capital Pride Festival on June 11th. Our first annual WWPH PRIDE Contest in poetry and micro-prose (250 words or less) opens on June 1st. Free to submit!

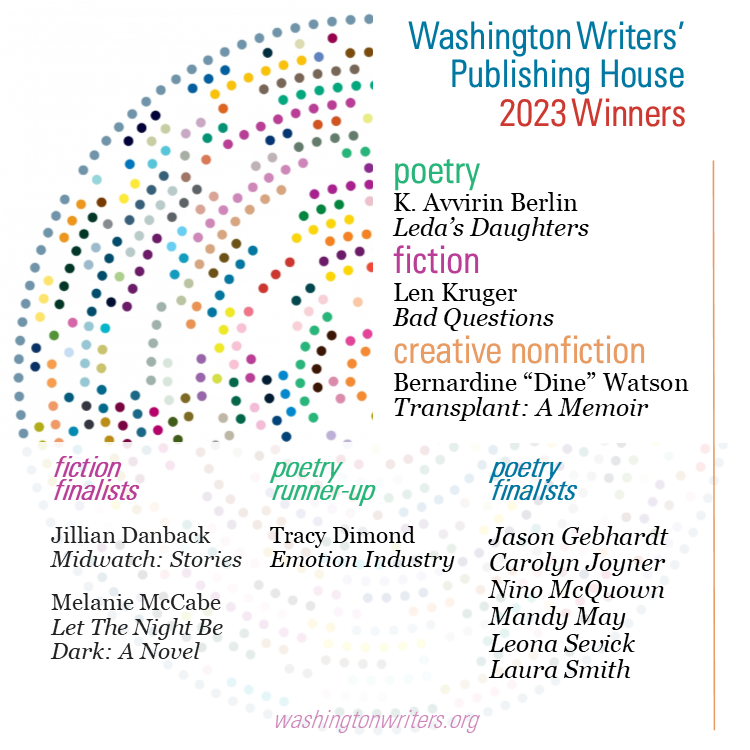

In case you didn’t see the news of our 2023 CONTEST WINNERS…here they are! OUR 2023 AWARD-WINNERS will be published on OCTOBER 3, 2023. If you are planning ahead, our 2024 Manuscript contests in poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction open on SEPTEMBER 1-November 1.

Purchase our award-winning books including the new edition of WHY I CANNOT TAKE A LOVER by Grace Cavalieri and ALTAMIRA by Myra Sklarew are available on our new affiliate page on bookshop.org . READ our WWPH TOP FIVE questions with Grace and Myra here. Special thanks to WWPH Fellow Lindsay Forbes Brown for the interview.

:

Happy 50th issue of WWPH Writes from Jona Colson and Caroline Bock (seen here at the recent Gaithersburg Book Festival)