WWPH WRITES ISSUE 77

WWPH Writes 77…and we are looking forward to seeing many of you this weekend at our Aguas/Waters events at Politics & Prose in DC, at The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore, and at The Writer’s Center in Bethesda! See below for details. Free and open to all. But first, read on to this issue’s poetry, ONLY, by Mike Reis and an excerpt from Kay White Drew’s STRESS TEST, an absorbing memoir about medical training in the 1970s. To paraphrase our eloquent poem this week, both works inspect a hard-hat Life.

Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents, WWPH

WWPH WRITES POETRY

Mike Reis is a writer and environmental historian whose poems have appeared in Narrative Northeast, North of Oxford, Woven Tale, Crossways, The Broadkill Review, The Raven’s Perch, Amelia, Northern New England Review, The Seventh Quarry, and the anthology Pandemic of Violence II: Poets Speak.

ONLY

Only: could we site-inspect

hard-hat Life before beginning it?

Unpack the convolute sub-lease,

mime and sock-puppet

the unbled radiator,

the propping the difficult door

by the burst shopping bags,

the breaking legs

off the new couch

against the unyielding jamb,

the too-rare swag of the suss arm

around the disappearing lover,

the midnight lava bombs

rained through the wafer-thin wall?

©Mike Reis 2024

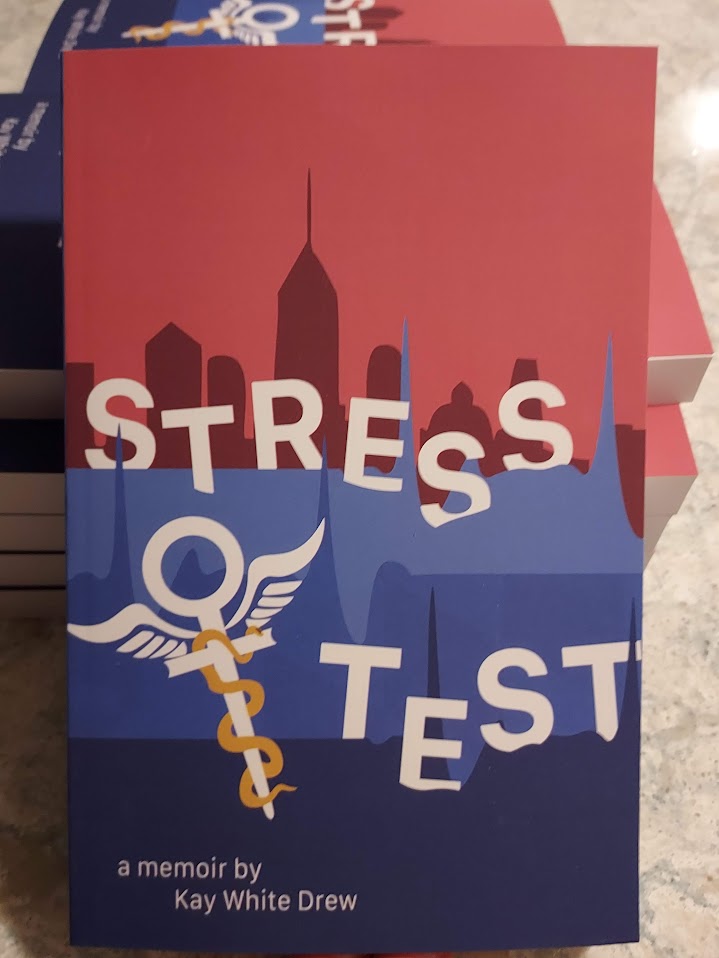

WWPH WRITES: A MEMOIR EXCERPT

Kay White Drew, a.k.a. Katherine White, M.D., is a retired neonatal physician. Her essays, poems, and short stories appear in several anthologies and online journals; an essay in the Loch Raven Review was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her memoir, Stress Test, was published in June by Apprentice House. She lives in Rockville, Maryland with her husband.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the summer of 1968, before my senior year of high school, my premed boyfriend took me on an unusual date. While many teenage girls might have recoiled from the experience, I found it fascinating, and it set the stage for the next several years of my life. Enjoy the prologue to my memoir.

STRESS TEST

“Shhh.” He put a finger to his lips. We tiptoed down a dark, concrete-floored hallway. Turning the handle slowly so as not to make any noise, he opened the door, took my hand, and led me into the empty space. I blinked as I stepped inside. The dim corridor opened onto a large semicircular room flooded with light from a wall of windows.

It was late August 1968, and the country was still reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy. Cities were going up in flames. Protests against the Vietnam War, forcefully quelled by Mayor Richard Daley and over twenty thousand police officers and National Guardsmen, were stealing the spotlight at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. I was pretty much oblivious to all this, being seventeen and ready to start my senior year of high school. My boyfriend, Lance, a sandy-haired, six-foot-six-inch pre-med college junior, had brought me to this place. Lance must have figured I wasn’t likely to be squeamish; my brother was in medical school, and I enjoyed Lance’s anecdotes about his vertebrate anatomy course. I’d dressed with care that morning, choosing a white dress I’d recently made on the family sewing machine, paired with some new earrings. Lance arrived at my house shortly before noon, wearing khakis and a short-sleeve button-down shirt, redolent of English Leather cologne.

“You look great,” he said, beaming at me.

The drive to Baltimore seemed a lot shorter than the hour or so it was supposed to take. While I was usually a quiet person, Lance always had a lot to say—about his dad’s clothing business, about “playing the ponies,” and sometimes about his aspiration to become a doctor. When I asked him how we would get into the hospital, he waved his hand dismissively.

“I know a guy,” he said with a grin.

Sure enough, his medical-student buddy Jim, a former fraternity brother, was waiting for us outside the main building of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. He greeted us, shook hands with Lance, and gave me a look of frank appreciation. Then he told us where to go and how to get there. We tiptoed down the hallways, not speaking above a whisper. I held my breath. Unaccompanied non-medical people weren’t supposed to be in the observation area above the surgical suite.

After sneaking through the maze of corridors, it took a while for our eyes to adjust to the operating room’s stark brightness. I hung back until Lance gestured me forward.

“Let’s sit up front,” he whispered, pointing to two plush fold-out chairs, like those in the movie theaters where he usually brought me on dates.

We slipped silently into our seats, and, wide-eyed, I leaned over to take in the vast surgical amphitheater on the other side of the windows. Lance placed a hand lightly on the small of my back and his voice resumed its normal boisterous volume.

“Jim said this was a gallbladder operation. It looks like they just opened her up.”

I recoiled at first: a human being, cut open on the operating table, her internal organs exposed to view. A faceless, inert, draped figure surrounded by busy anonymous people in gowns, masks, and rubber gloves, wielding surgical instruments like a bunch of car mechanics with wrenches. I flashed on images of sides of beef in butcher-shop refrigerators, or coroners examining corpses on TV crime shows. But then Lance pointed out the woman’s liver, deep red and glistening, as the surgeon started to tie off the small greenish-brown sac attached to it, the gallbladder. My revulsion gave way to curiosity and a sense of wonder.

“Wow! So that’s what we look like inside.”

“Yeah, pretty neat, huh?”

I was stunned by the scene unfolding below us. The patient was anesthetized, asleep on the table, and yet—blood kept coursing through her body, fluids kept moving through her intestines, even while the doctors and nurses were getting rid of the expendable organ that wasn’t working right. What did her beating heart look like? Was it the same shade of red as her liver? And her lungs, rising and falling gently within her chest to the rhythm of the ventilator: did their surfaces gleam, too? Did they really look like sponges, as we’d been taught in 10th grade biology? There were occasional glimpses of bright red blood as vessels were cut and then stitched or cauterized. The blood, the organs of a living human being—they were beautiful, in a way I never would have expected. And a few hours from now, the woman on the table would be awake and talking, relieved of the pain that had brought her here. If this wasn’t a miracle, what was?

I reached for Lance’s hand and gave it a grateful squeeze as I kept my eyes on the scene below. I wanted to know more about what went on inside our bodies. I wanted to know what to do when something went wrong, how to fix it.

I wanted to learn what those people in the operating room knew….

This excerpt from Stress Test was reprinted with permission of its author and is now available everywhere books are sold. Support your local bookstore and find it here at bookshop.org. More about Kay White Drew here.

©Kay White Drew 2024

WWPH NewS

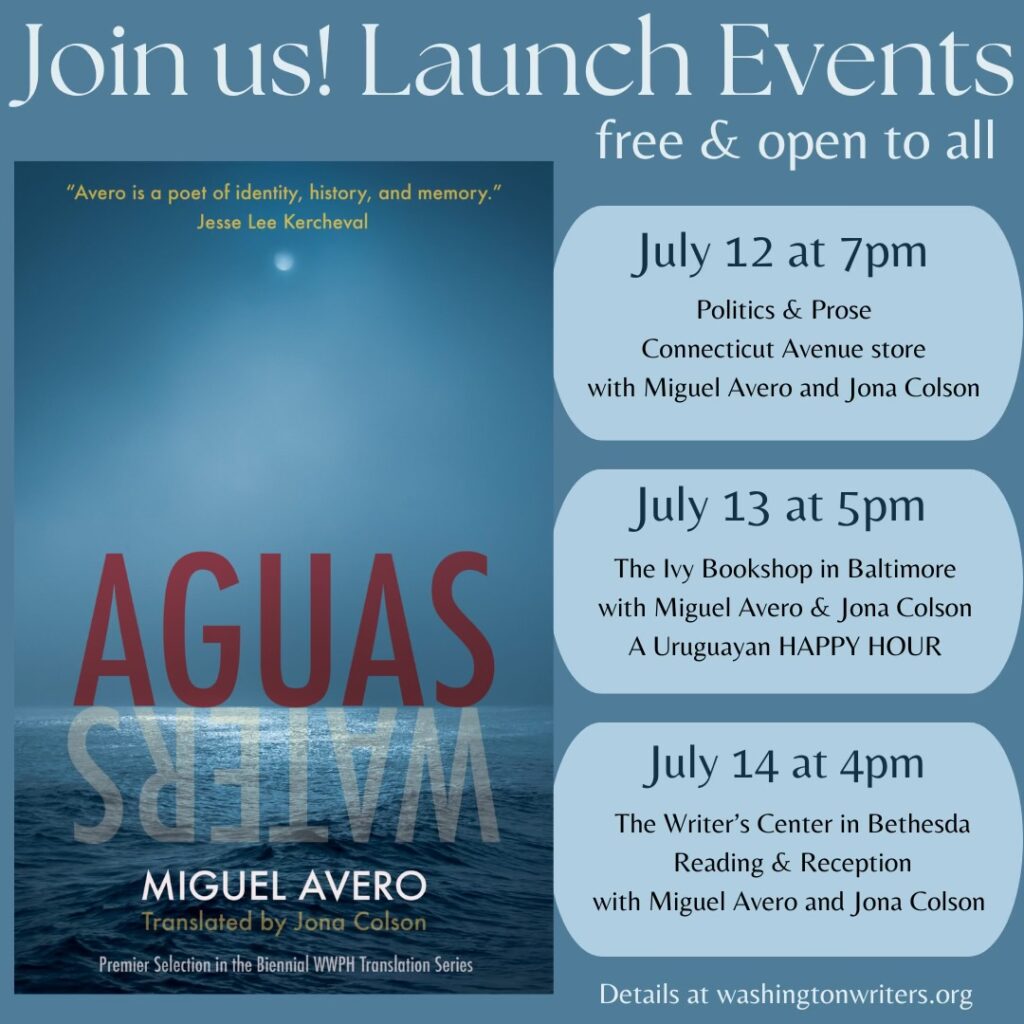

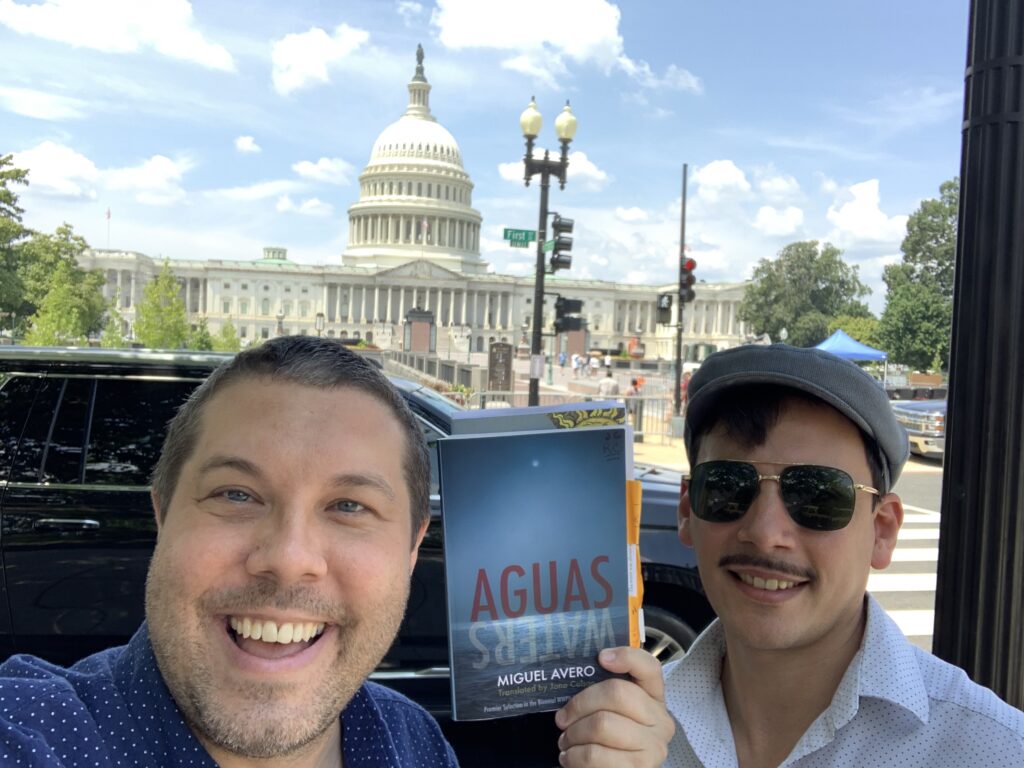

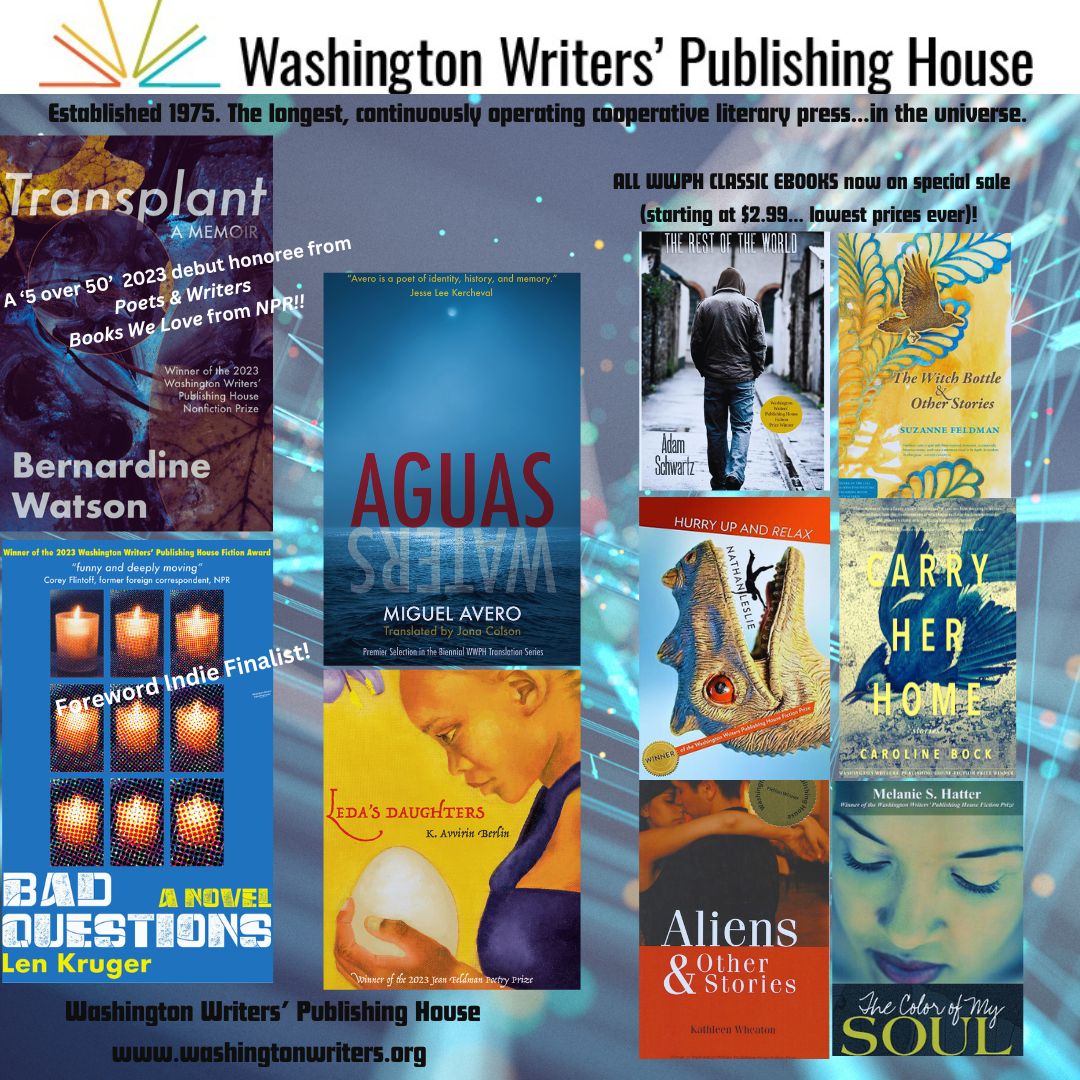

JOIN US this weekend to celebrate AGUAS/WATERS by Miguel Avero and translated by Jona Colson. As the poet and translator share in this CITY PAPER interview, this collection was more than a decade in the making! It’s the premier selection in the new Biennial WWPH translation series. This will be your only chance to have a signed first edition by the poet (unless you are traveling to Montevideo, Uruguay!). We look forward to seeing you…

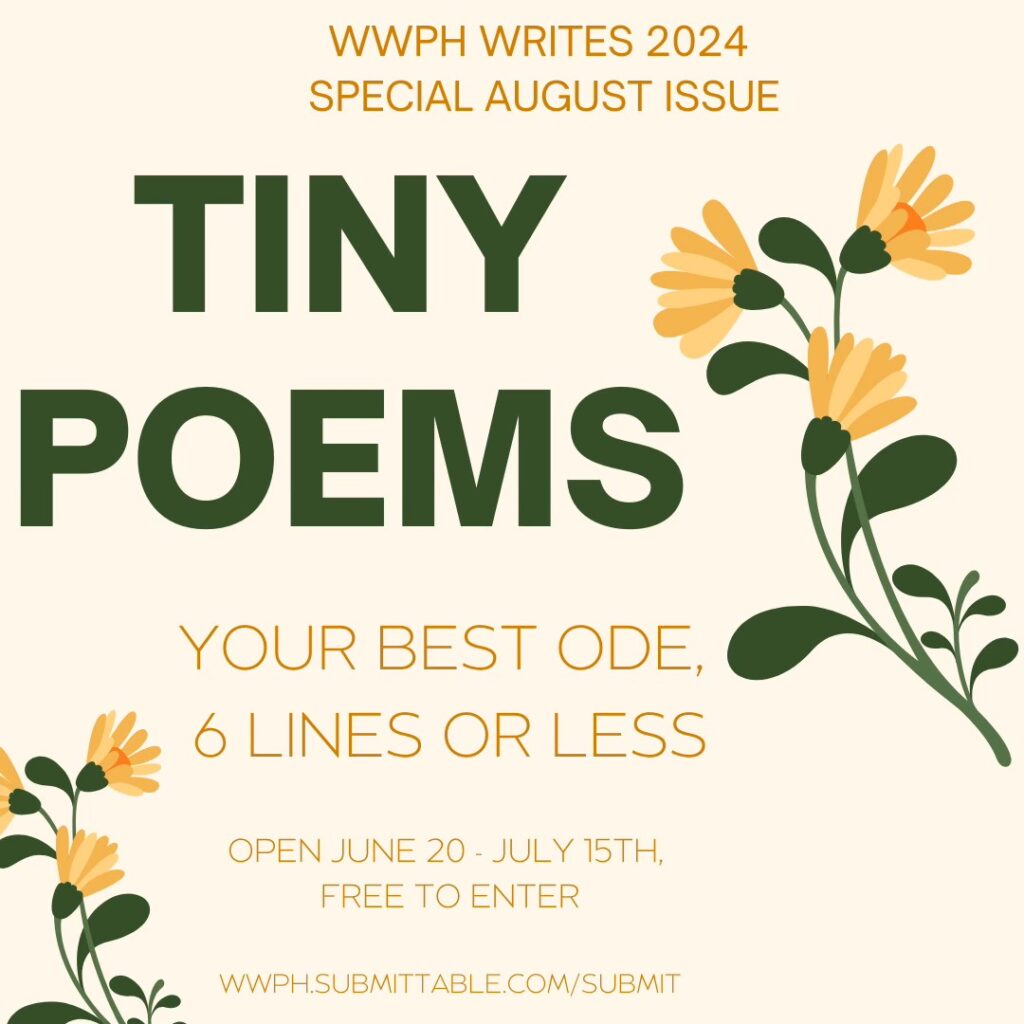

O, DEAR READERS, you have sent us multitudes of TINY ODES. We will publish all our favorites in August. Free to submit. The deadline is JULY 15th at 11:59 pm.

Our 2023 Award-Winning Books continue to garner attention and acclaim. They are available everywhere books are! Support your local independent bookstore and your WWPH by ordering them from www.bookshop.org. And our classic ebooks are now on sale!

Insider news…this September, we will be opening submissions for our new anthology AMERICA’S FUTURE. Stay tuned for more details! More insider news: On September 17th we will undertake our second WWPH LITERARY SALON at the National Arts Club in Washington DC. Caroline Bock and Jona Colson will host this free evening event featuring several other notable DC-based writers (soon to be announced!). It’s all made possible with a generous grant from the DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities. Keep reading WWPH Writes for more details on these exciting happenings!