WWPH WRITES ISSUE 94

WWPH Writes 94… and a poet returns to the Washington Writers’ Publishing House…Jane Schapiro published her first poetry collection, Tapping This Stone, in 1995 with WWPH, and is back with a haunting poem, The Warm Line: The Hand. Her work is alongside a gripping excerpt from The Churning, a novel-in-progress by Jyoti Minocha.

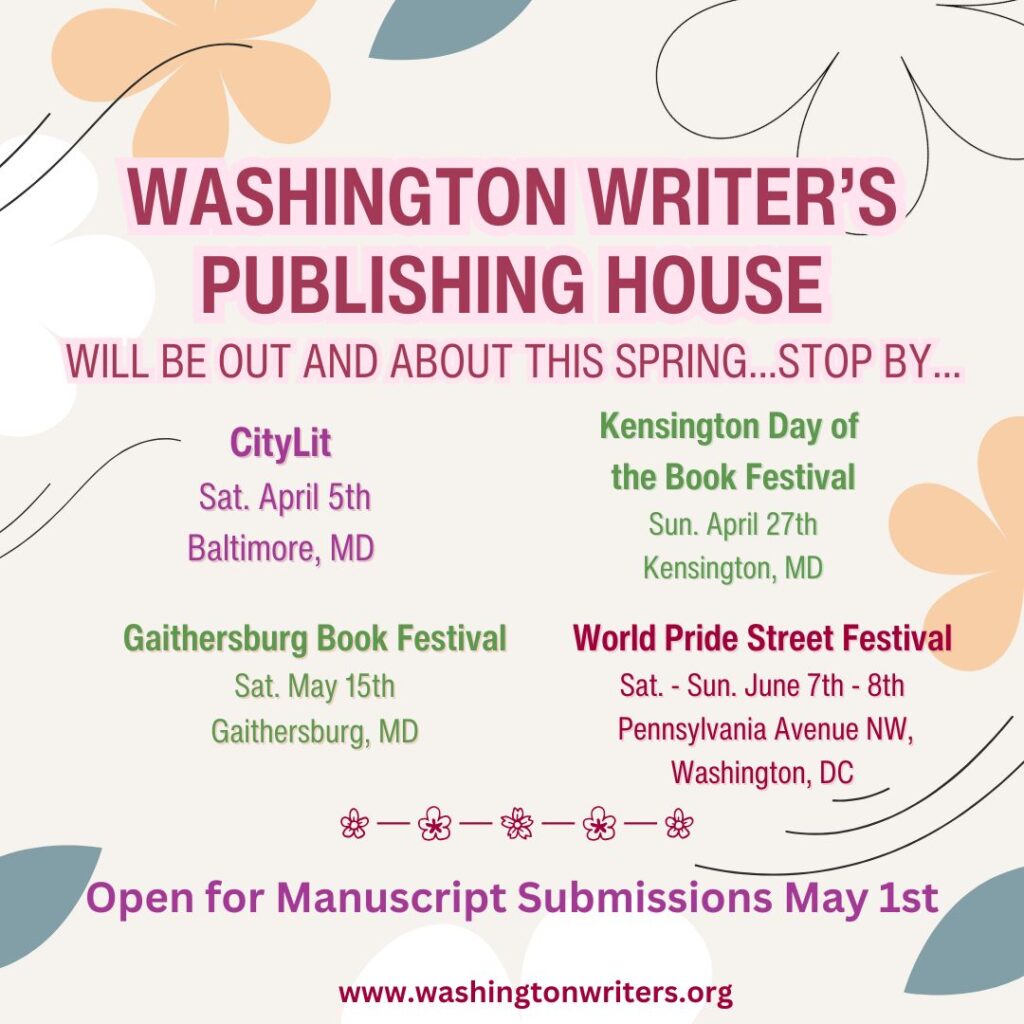

Your Washington Writers’ Publishing House will be at several upcoming literary/book festivals this spring starting with the CityLit Festival in Baltimore on Saturday, April 5th (see below for all the events). Make sure you stop by our table and say hello.

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents/editors

Washington Writers’ Publishing House

WWPH WRITES Poetry

Jane Schapiro’s work has appeared in numerous journals. Her first book Tapping This Stone was published by WWPH in 1995. She is the author of two other volumes of poetry: Warbler which won a 2020 Nautilus Award, and Let The Wind Push Us Across. Her chapbook Mrs. Cave’s House won the Sow’s Ear Poetry Chapbook competition. Her nonfiction book Inside a Class Action: The Holocaust and the Swiss Banks was published by the University of Wisconsin. She lives in Fairfax, VA.

The Warm Line: The Hand

(aka Emotional Support Line)

“The Hand called,” a volunteer wrote in the notes.

Many of us have taken her calls,

listened to her monologue:

her hand’s deformity, her long-ago stroke,

people at church making fun of her hand,

people in book group making fun of her hand,

people everywhere making fun of her hand.

Her hand is the center of her circular self,

the point that guides her compass around.

“I love my hand,” she announces,

as she orbits her tale.

Once, as she was describing her twisted palm,

my dog, barking, bolted through the screen door.

Holding the phone, I ran into the street.

My dog got out, I screamed,

and from my hand, a voice rose up:

Calm down, get a bone, your dog will come home.

In a flash, The Hand drew back,

I heard a woman

talking to me.

©Jane Schapiro 2025

WWPH WRITES a Novel-in-Progress Excerpt

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is an excerpt from my novel-in-progress THE CHURNING. Set during the Partition of British India into two states, India and Pakistan, purely along religious lines, it follows the story of Ram, the son of a prominent Indian family, who travels to England in 1939 to study and is caught off guard by the outbreak of World War II. He returns to his hometown, Lahore, in 1947, a few months before the country is partitioned, and law and order breaks down. Unknown to his family, he has fallen in love and become engaged to an Englishwoman. He brings his finance, Johanna, to get his parents’ blessings; however, his mother objects strongly to this engagement since Ram had been betrothed as a child to their neighbor’s daughter, Sharmila. While the family drama rages inside the walls of their home, mayhem reigns outside as the province is divided into two, and religious minorities are chased out, or butchered.

This particular excerpt deals with a part where Ram’s family is targeted because they are Hindus. Outside the walls of the house, a brisk trade has begun in the abduction of women, particularly poor ones, whose families wouldn’t have the resources or means to find them. A maid in Ram’s household is targeted, and when Johanna tries to prevent the abduction, she is taken as well. However, the owner of the brothel to which they are brought, a madam called Zainab Bibi, realizes that Johanna, an Englishwoman, could be a liability—the British still carry some residual authority in the area. She tells her strongman, Mehboob, to ‘fix the problem.’ — Jyoti Minocha

THE CHURNING

Mehboob regarded her with a mixture of dread and curiosity. He had never killed a woman before. Let alone a gori. He didn’t like this part of his job at all. Men were ok—he had disposed of enough men, nasty, brutish creatures who begged for mercy at the end but got none because Mehboob knew how many innocent souls they had murdered. Or so he believed whenever he disposed of a troublesome pimp, which happened less and less now since Zainab Bibi simply had to use the threat of her high-level connections to subdue the competition.

But a woman?

Should he just let her go? She wouldn’t know the way back, anyway. No, he had never disobeyed an order from his mistress. He reached out impulsively and yanked her blindfold off.

Johanna was shaking her head fiercely, crying “No, no, no, no!” With her shorn head and terrorized eyes, she reminded him of one of the sheared lambs he would take to slaughter in the back courtyard on Bakr Eid.

Suddenly, he wanted to see her whole face. He would make up his mind after that. Maybe he would take her much further out, a day’s journey even, and leave her in some hinterland where it would be almost impossible for her to find her way back. Killing a woman felt like an abomination, and he had developed a knot of anxiety in his stomach.

He took off the gag.

Johanna gasped and licked her lips wildly, panting.

“Please, please, please!” she pleaded, extending her bound hands to him. Her eyes shone, filled with tears of desperation that reflected the moonlight.

“No! No! No!” Mehboob said loudly pointing back in the direction they had come from. “No away, no go!” His vocabulary included a dozen more English words including: “Run,” “Idiot,” and “Fool,” all learned whenever Zainab Bibi directed them at him, but these were the closest to explaining that there was no place for Johanna to go now.

Mehboob had never seen a gori up so close. On an impulse, he reached out, and Johanna flinched as his rough brown finger stroked her cheek. This was what white skin felt like he thought, soft as a dove’s feather.

Strangling her would be like strangling a dove—it wouldn’t take a lot of pressure, just a thumb’s width of it, but how would he be able to do it with her frightened eyes rolling at him like that?

Mehboob’s preferred method of killing had always been with his outsize hands: the enormous strength in them when they pressed down on a vulnerable throat closed the windpipe immediately, and his victims were no match for his hulk as they kicked and beat desperately at him. But he couldn’t do that to this beautiful gori. No, a sudden idea sprang into his brain. The Ravi wasn’t too far away, a mile or two. He would drown her with a heavy stone tied to her ankles. That way, he wouldn’t be witness to her mute, brutal struggle to survive, limbs thrashing and flailing, heart bursting, her cries leaving a trail of bubbles that would rise to the surface and pop while the river would move swiftly on. The weight attached to her feet would sink her straight to the bottom, out of sight.

Johanna fell to her knees her head bowed, and her bound hands stretched out in front of her in a pleading gesture.

“Look, they are hurting. I’m bleeding!” she cried.

Mehboob looked down at her wrists. They had been bound so tightly by him that they had reddened and were swollen around the edges of the rope, with drops of blood oozing where the rough jute sliced them. Would it matter if he gave her some relief before he disposed of her? She wouldn’t be able to overpower him or run away, even if she tried to. He was too strong and too fast for her. He would put her back in the tonga and tie the canvas flap and drive to the river.

He lifted her under the arms, off her feet, and carried her to the tonga. He put her on the bench and then, almost as an afterthought, removed the rope around her wrists.

“Thank you!” Johanna burbled through her tears. She looked at Mehboob, pinning him with her desperate, pleading eyes. “Please let me go. For God’s sake, for Allah’s sake. Don’t do whatever you are planning to do.”

Mehboob didn’t understand anything except please and God and Allah, and he jerked the canvas cover hastily and tightly secured the sides. The gori’s mention of God had rattled him. He had been brought up by a pious mother who had invoked Allah a thousand times a day, and as soon as he could walk, Mehboob had worshipped her instead of Allah. Even after she had died and left him an orphan at the age of ten, he would hear her voice in his head, reciting the ninety-nine names of Allah whenever the Muezzin called out prayers. Women who invoked God were a particular vulnerability of his.

©Jyoti Minocha 2025

Jyoti Minocha is a writer based in the DC metro area, living in Virginia with her husband and two daughters. She teaches English at Montgomery College in Maryland and frequently freelances for online magazines. History and historical fiction have always been a passion, and she decided to work on a novel relevant to her family’s roots, partly because she wanted her two daughters to learn about their ancestry.

WWPH NEWS

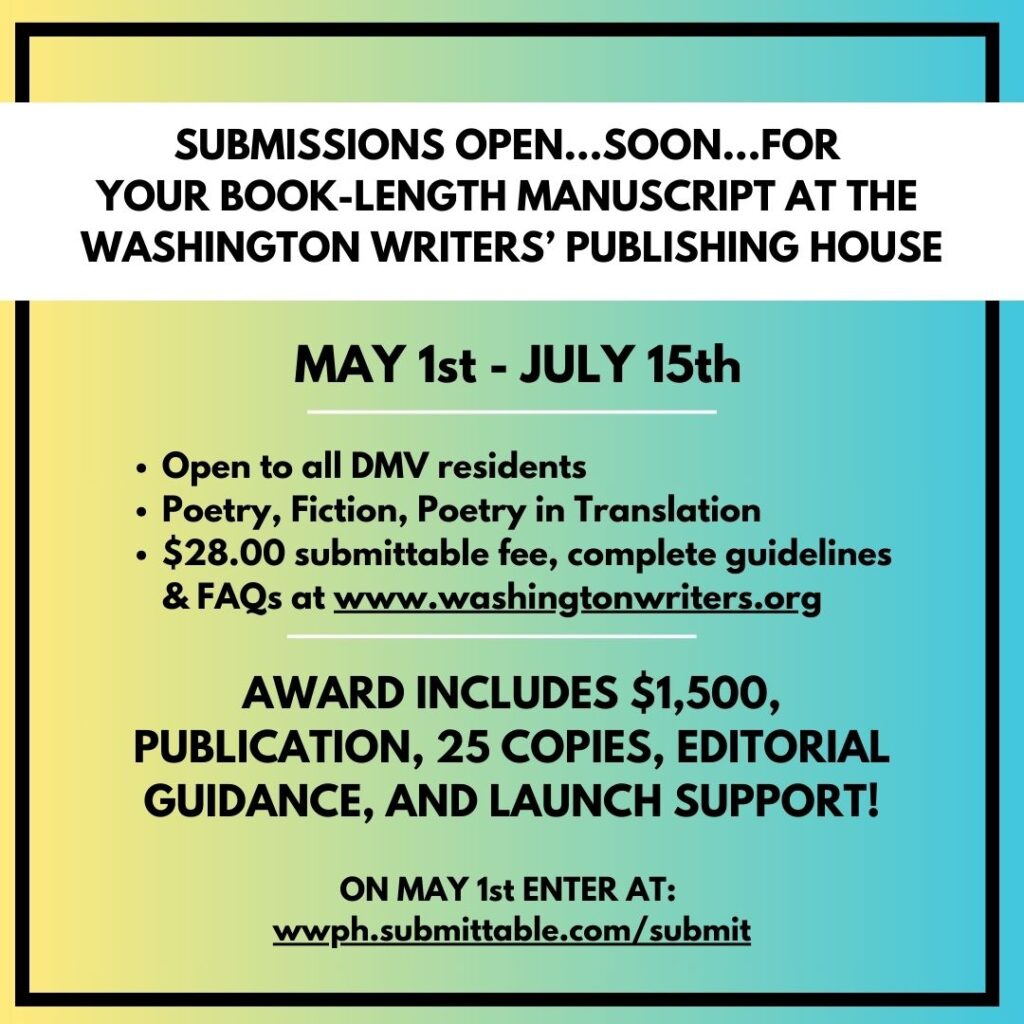

Stop by our table at one of these upcoming events. Learn more about publishing with us…our book-length manuscript contests open on May 1, and we are eager to read your poetry, fiction (novel or short story collection), and poetry in translation.

INSIDER NEWS… if you are considering submitting your book-length manuscript to WWPH, check out our guidelines and FAQs (new for 2025!) here.

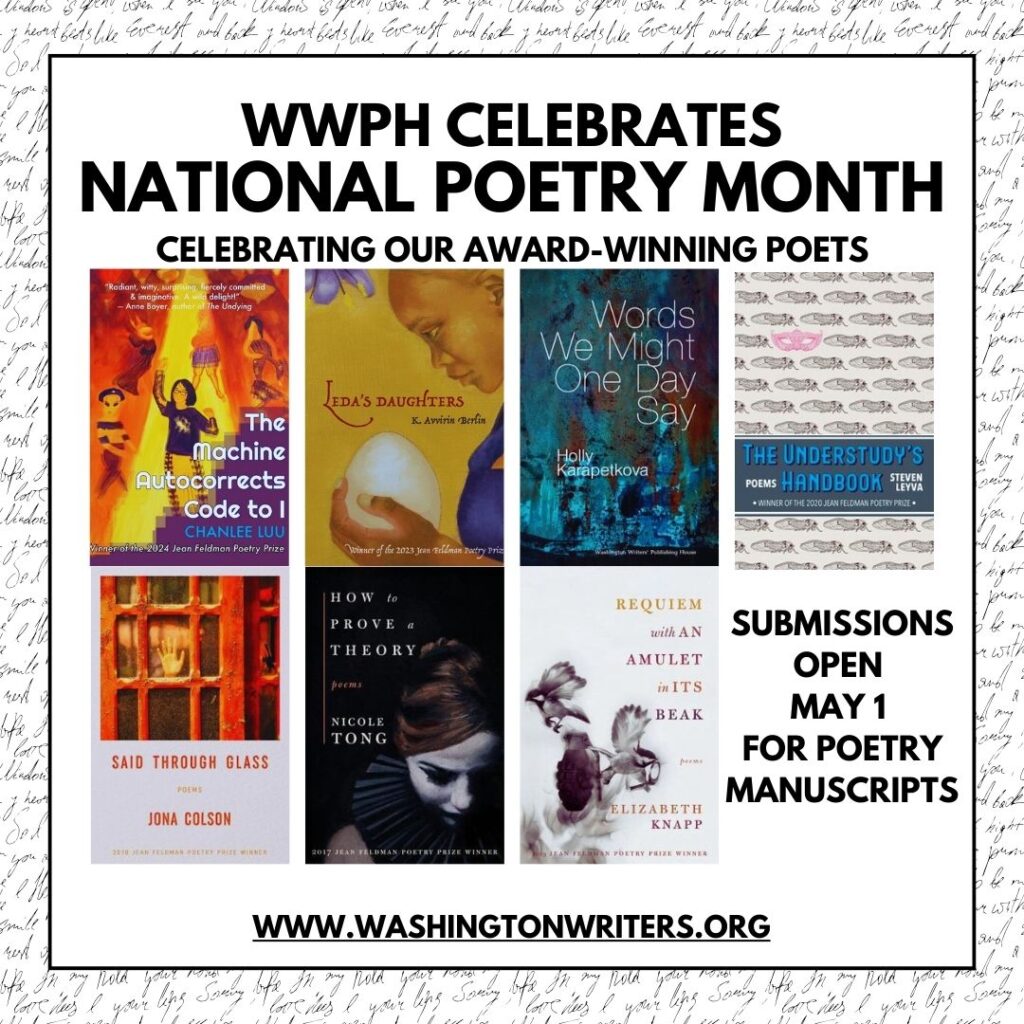

April is National Poetry Month… and we are ready! Find our Jean Feldman Award-winning poetry collections everywhere books are sold! Here is a link to our bookshop.org affiliate page:

WWPH WRITES is open for submissions! We now pay $25.00 for poetry (up to 3 poems) and prose (up to 1,000 words of fiction or creative nonfiction). Free to submit! More details at our Submittable page here.

SOLIDARITY, all! We’re grateful you are part of the Washington Writers’ Publishing House community!

Keep reading WWPH Writes for upcoming news on our two (yes, two) new anthologies!