WWPH WRITES ISSUE 84

WWPH Writes 84… features two moving, contemplative works, EYES OF MONET, a new poem by Lora Berg, and TIME PASSES, a creative nonfiction essay excerpt from Andrew Bertaina.

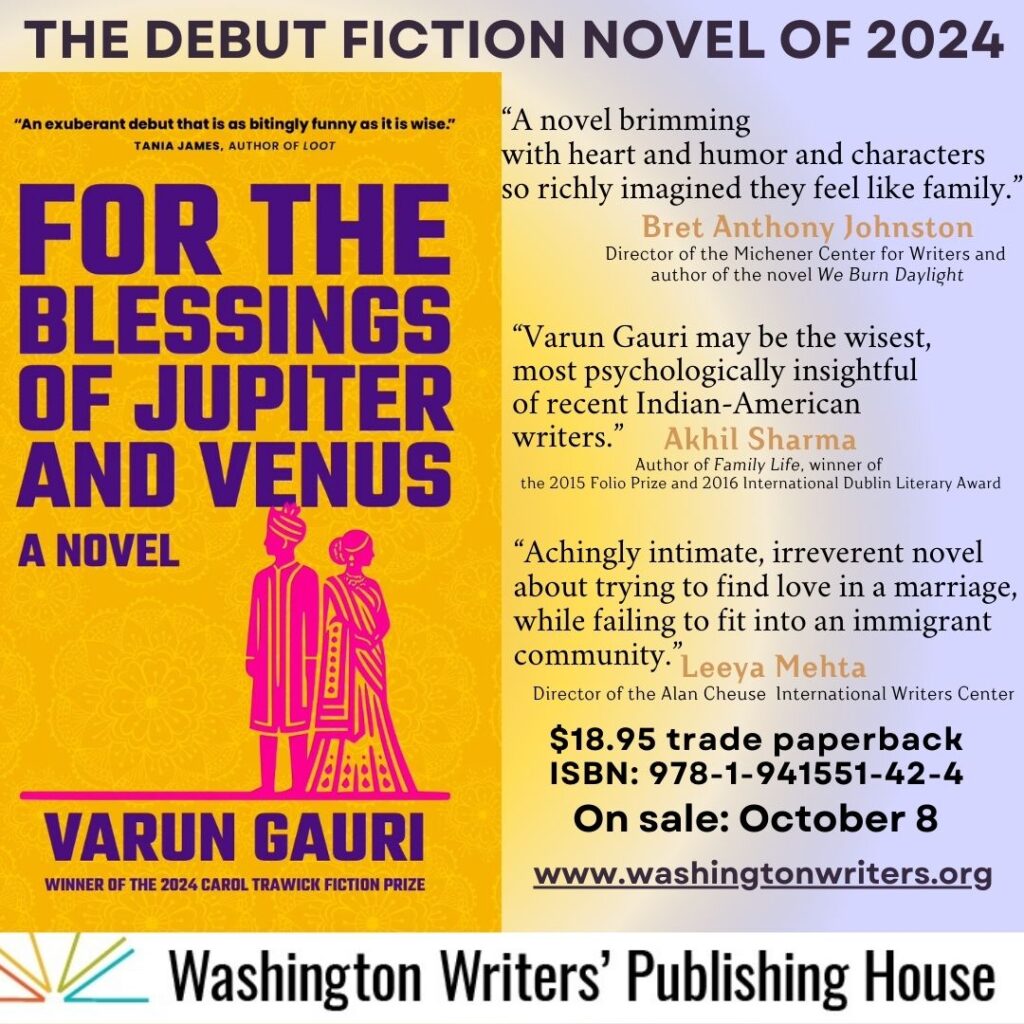

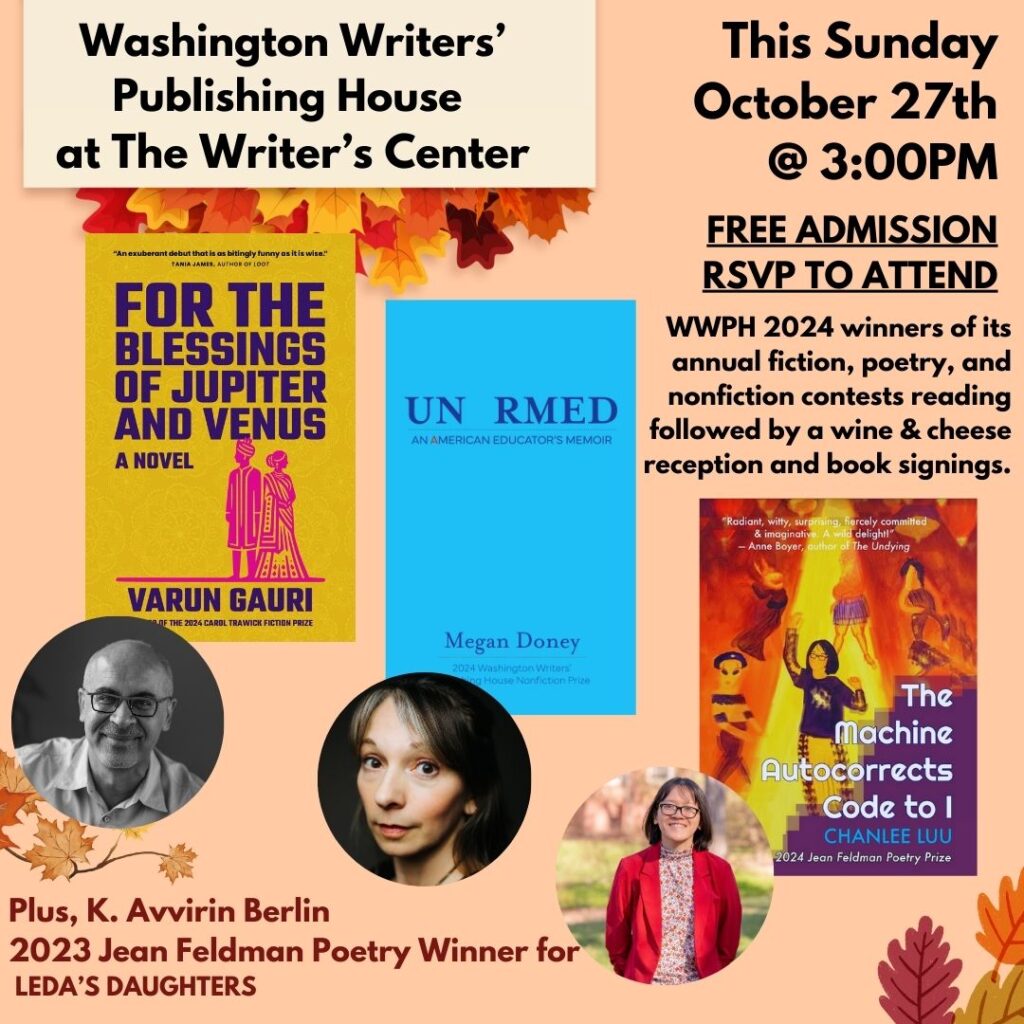

Join us at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda this Sunday, October 27th at 3 pm as we celebrate the launch of our 2024 award-winning books… For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus by Varun Gauri; UNARMED: An American Educator’s Memoir by Megan Doney; and The Machine Autocorrects Code to I by Chanlee Luu. Free and open to all, our Writer’s Center event includes a wine and cheese reception, so please let us know you are coming with an RSVP here! We will also be on hand to answer questions about how you can be published with the Washington Writers’ Publishing House and how you can apply for a paid WWPH Fellowship for 2025.

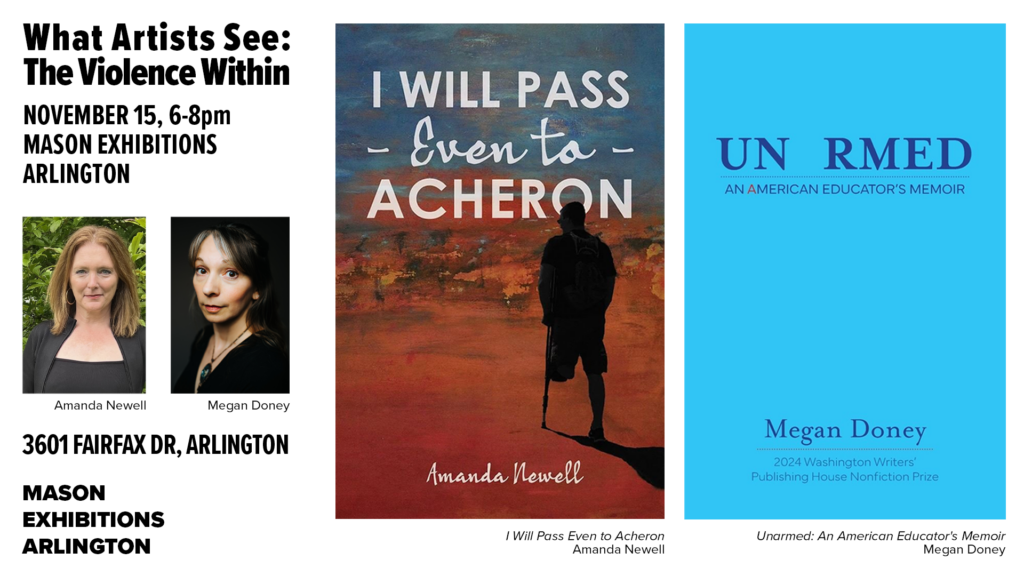

And there is more. November 15 at 6 p.m. marks our first major event with the Cheuse Center at George Mason University—and it is a timely and important event—WHAT ARTISTS SEE: The Violence Within at the Mason Exhibitions gallery in Arlington, VA. Please join us for the interactive exchange of literature, art, and ideas. It is free and open to all. See below for more details.

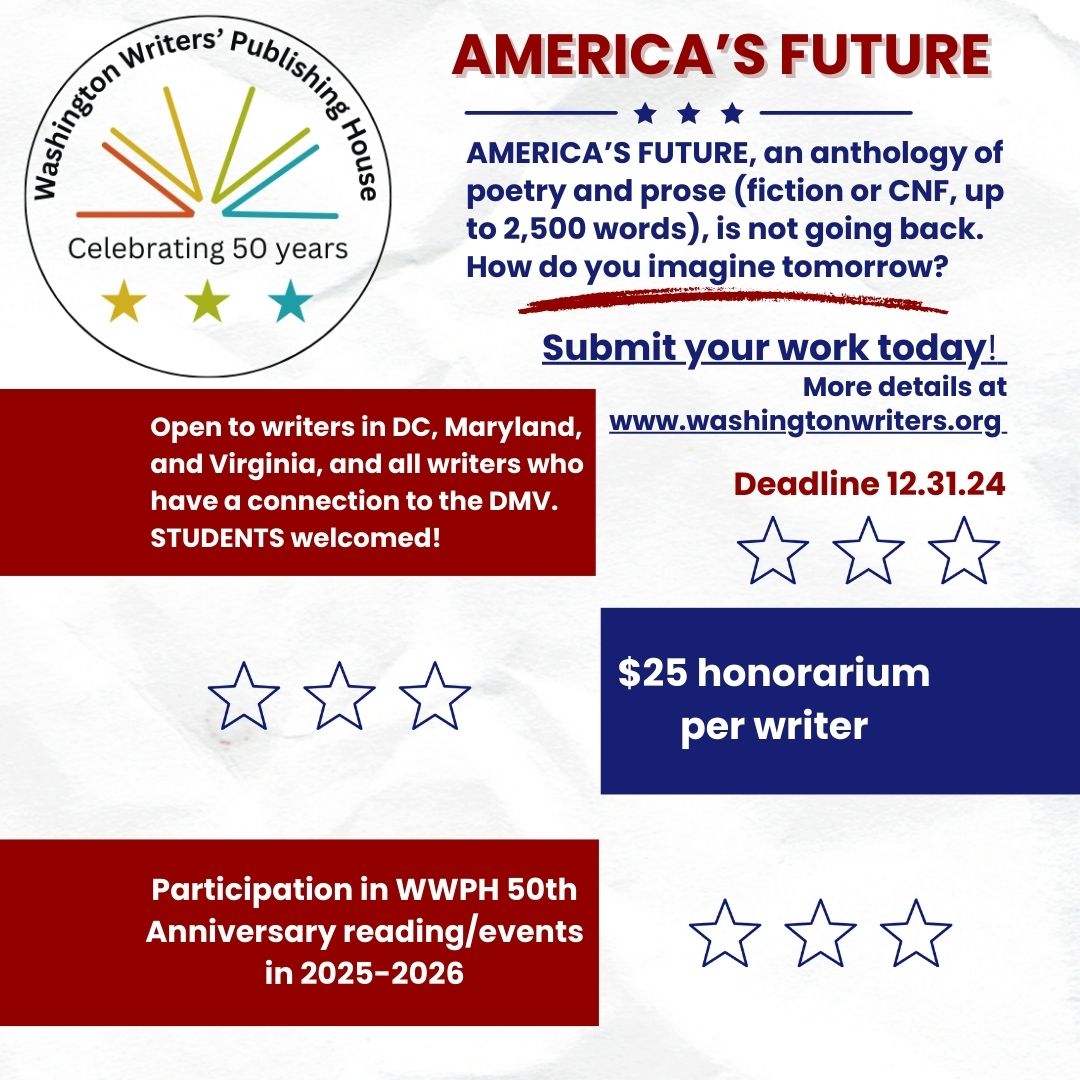

Our 50th-anniversary anthology, AMERICA’S FUTURE, is now open for submissions. We invite you to send us your work now. More details are below.

Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents and co-editors Washington Writers’ Publishing House

WWPH WRITES Poetry

Author of The Mermaid Wakes, Lora Berg writes with a light touch. Her poems appear regularly in literary journals. Lora served abroad as a cultural attaché. Former poet-in-residence at Saint Albans School with a Johns Hopkins MFA, she joined Lighthouse Poetry Collective 2023. Lora is a grandma in a vibrant multicultural family. Photo credit: Jessica Raimi.

EYES OF MONET

Aging eyes

mismeasure depth,

the distance

between objects

says my optometrist,

and I’m not surprised.

Long ago seems close,

yesterday, outlying.

Maybe I could see

Monet’s way, gaze past cataracts

as clematis, poppies, roses

float and meld.

or Handel’s way,

even as the organ

keys merge

into a wisp,

cantatas waken

in one dark stroke,

brush of ink on silk,

angel’s riff, wild horses.

Train yourself,

the optometrist advises.

I already see

harp strings blur

into glissandos, youth

diffuse into age,

delphinia into

a swathe of ocean.

©Lora Berg 2024

WWPH WRITES Excerpt

Andrew Bertaina is the author of the essay collection, The Body Is A Temporary Gathering Place, and the short story collection, One Person Away From You. His work has appeared in The Threepenny Review, Prairie Schooner, Witness Magazine, and elsewhere. His essays have been listed as notable in three editions of The Best American Essays. More at his website here.

An excerpt from the acclaimed collection The Body Is A Temporary Gathering Place from Autofocus Books.

Author context:

This excerpt is from my essay, Time Passes, which is a mediation on how we experience the passage of time scientifically, culturally, and in literature. The essay also deals with my own obsession with how I pass my time, particularly as a parent of young children in an addictive and distracted culture. Beyond that, the essay is a personal meditation, which means that it’s dealing with memory, the moments that seem significant or keep recurring in my mind, whether that be a trip to Italy or a memory of my mother. The excerpt is from the opening of the essay when I was trying to invite the reader into my mind, its oddities, and peculiarities as I started to ruminate on how we experience the passage of time.

TIME PASSES

I remember endless summer days as a child–days spent in blistering California heat, roaming through the grass, climbing the towering cumquat tree, holding my finger out to crickets, or letting out a long parabolic rope of pee onto the juniper. Why did the summer days–the crickets chirping, the ice clinking in a glass of lemonade seem to distend, until they fill up large recesses of memory?

Like any good essayist, I set out to answer the question of time’s riddle. Like most good questions, it turns out that the answer is multi-faceted and not entirely conclusive. The explanations range from the mathematical to the psychological and neurological. The typical hypothesis is that our young brains are rapidly encoding new experiences, every scent of a rose, every buzz of a fly has the potential to create a new memory. Just this week, my own children were shouting about a bee that had flown into the car, squirming in their seats like wild animals.

“That’s not a bee,” I said. “That’s just a fly. And even if it was a bee, they don’t bother unless you bother them.”

In my experience, the discovery of the bug would have resulted in me rolling down the window and continuing to think about the structure of my day and logistics on the weekend. To the children, the fly was a novel experience. It wasn’t even a fly. It was a havoc-causing bee.

The logarithmic explanation also explains our differing perceptions of time. The explanation runs thusly, when you are two years old, a summer is ⅛ of your lived experience. Thus, a summer, or even a day can feel like a long stretch of time relative to the total sum of your life. For an adult of forty, a summer feels like 0.00625 percent. By this explanation, which feels a bit like breaking down why a joke is hilarious and taking the piss out of it, and this essay, see line one, is pro piss, it makes sense that our experience of time as a child feels elongated and drastically truncated as we age.

The last explanation comes from a recent study at Duke University. In this study, it was found that brain degradation contributed to a perceptual difference in how the young and old experience time. Because new brains are much more efficient at processing and encoding information, there is a density to time, a rapid-fire sense that everything is happening all at once, which declines as our brains’ ability to encode declines as well.

But why discuss time anyway? Isn’t it the job of an essayist to bring time to life, to mention the screened-in porch and the loose fence board we all used to sneak under to travel between backyards? I don’t entirely know why I’m fascinated by time. Sometimes I assume that everyone else is as baffled or interested in precisely the same sorts of things I am, but I’ve learned that isn’t true.

What is time exactly? A difficult question, and well beyond the scope of what I intend to write as I possess no special knowledge of relativity or quantum mechanics. My investigation involves the substance of how we spend our time, ensconced at a particular moment in time in the twenty-first century. What is time? It is that which passes by in any given American urban life like mine–retrieving the children from school, passing through reams of traffic, pedestrians high-tailing it through crosswalks and bikes vaguely following the laws of traffic, the row of azaleas and coneflowers that line the mulch on my short walk to the gym. Time is that which is spent. Or perhaps spent is the wrong phrase, as though we had a choice in the matter. Time is sitting on the front porch steps, bony butt aching, while the wind rattles the limbs of a distant oak, and the children are away for the night, spending the evening with their mother. But I am also concerned with the oddities of time, the way that it warps around a black hole, the way that it influences an essayist recording the patter of thoughts or how the impressionists recorded its passage by shifting the way that light moved through the trees.

Sometimes I’ll find myself between sentences in this essay, brain idling, living in the interstices that comprise most of our lives, and I’ll click back to my prior tab, which affirms the final score of the game was 87-81. This is largely due to the compulsive way I pass time, checking and rechecking tabs on the internet, always with the nagging sense that I’ve missed something. I’ve read that the internet is addictive, in part because we are information-seeking creatures, and we’ve now been provided an endless repository to mine for uselessness. Implicit in the prior statement, perhaps problematically, is that our lives should have some use beyond checking the internet for basketball scores and cat memes. This implicit assumption is that our time should be spent meaningfully. Should time be spent meaningfully? And if so, why? Is it because we will all one day be gone?

Our lives are linear, even if we don’t always experience them that way. I often spend minutes in mindless reverie, imagining an e-mail I’ll send to a friend I’ve lost touch with, all the while passing the present moment, willfully not attending to it. Even if I imagine my parallel lives, seemingly breaking the wheel of time by moving sideways or backward through it, or if I indulge in memory, my mother’s fiery red hair, a day spent in childhood dropping water on a teeming mass of ants, contemporaneous time still plods inexorably forward. And all our history in time trails behind us like the contrails of a comet—broken marriages, broken fingers, broken promises, a mid-day cup of tea on the Ponte Vecchio.

©Andrew Bertaina 2024

This excerpt from Time Passes originally appeared at Post Road. It is published in The Body Is A Temporary Gathering Place from Autofocus Books. Read the entire collection. Purchase your copy here at Autofocus Books.

WWPH INTERVIEW

WWPH INTERVIEWS: VARUN GAURI winner of our 2024 Carol Trawick Fiction Award for his debut novel FOR THE BLESSINGS OF JUPITER AND VENUS. Read the answers to our top five questions here.

PURCHASE his acclaimed novel everywhere books are sold including here: Bookshop.org

WWPH NEWS

One more reminder! JOIN US on Sunday, October 27 at 3 pm the Writer’s Center in Bethesda. Reading with our 2024 award-winning writers followed by a wine and cheese reception. Free and open to all.

Submit your poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and works in translation to AMERICA’S FUTURE. Detailed prompts and guidelines are available here. WE ARE NOT GOING BACK.

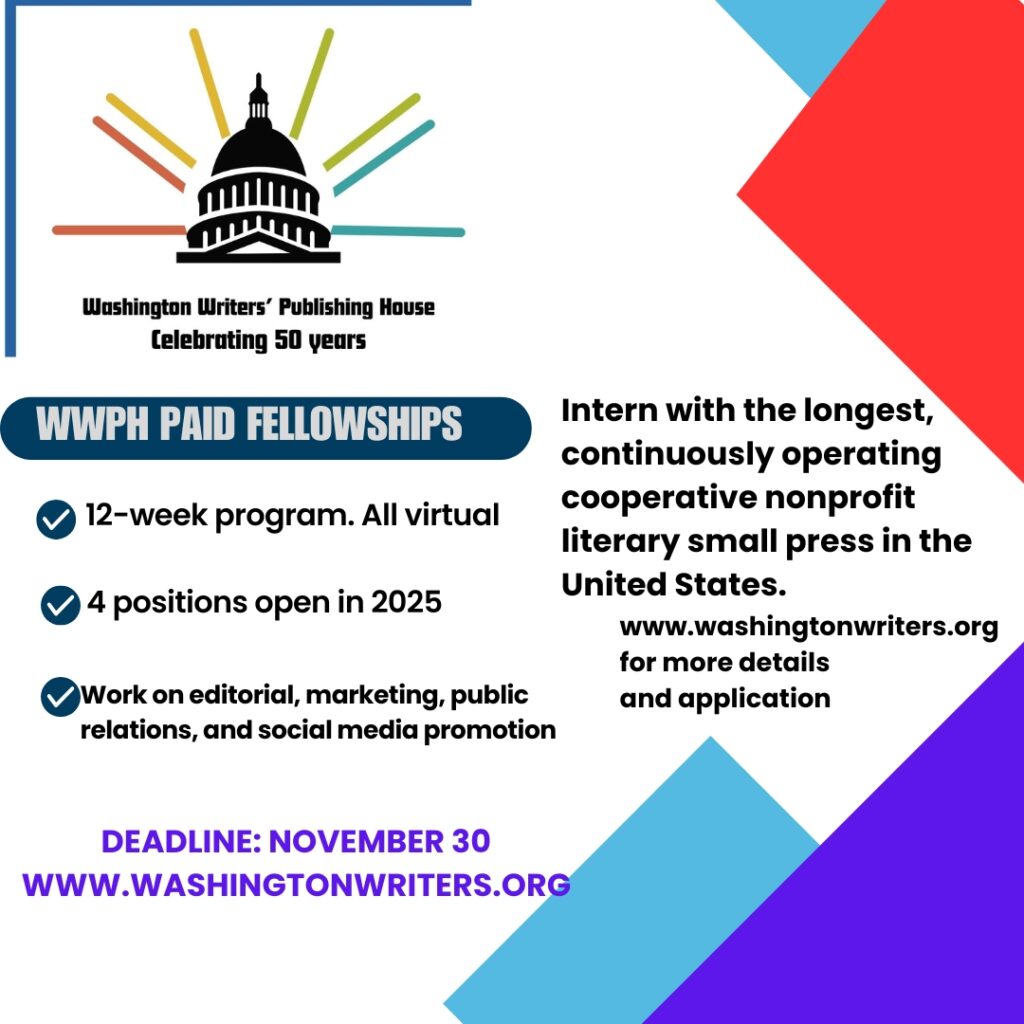

WWPH is offering paid WWPH Fellowships to interested undergraduates, graduate students, or recent graduates. A big thank you to Dr. Jean Feldman for underwriting this program. More information and an application can be found here.

MARK YOUR CALENDARS FOR THIS MAJOR NOVEMBER EVENT! WHAT ARTISTS SEE: THE VIOLENCE WITHIN… AN EVENING OF ART AND LITERATURE in conjunction with the Cheuse Center at George Mason University. Megan Doney, winner of WWPH 2024 Nonfiction Prize, and poet Amanda Newell. The backdrop of this event is Mason’s collaboration with South African print-making now on display at the Mason Exhibitions gallery in Arlington. The event will include readings and participation by the audience. Themes include gun violence and how we perceive threats to ourselves and our societies. The framing of South African and American artists and audiences will allow for an international exploration of creativity and violence. Presented in collaboration with your Washington Writers’ Publishing House.

More details here. ALL INVITED.

]\

Thank you all for being part of the WWPH community!