WWPH Writes 92… captures sharp dualities with THE KEY, poetry by Karla Daly, and CRIME SPREE AT THE IGA, creative nonfiction by Paul Grussendorf.

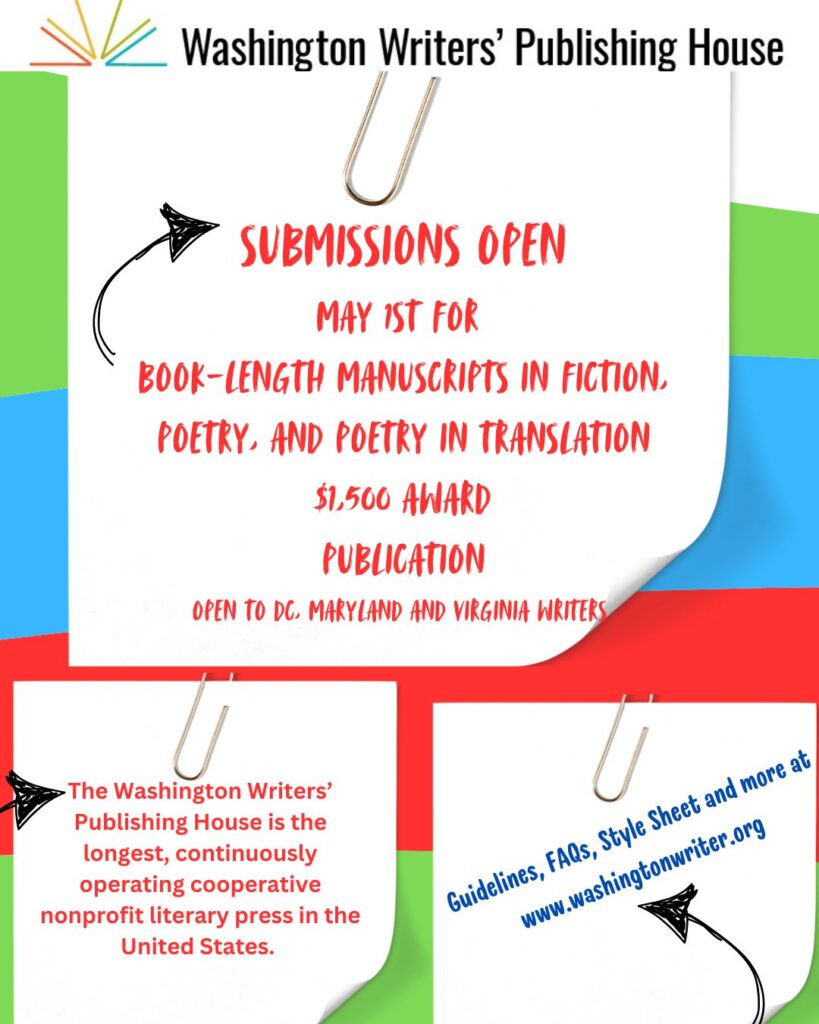

For all of those who like to plan ahead, we open submissions for our annual book-length manuscript contests on May 1st. This year, we are seeking fiction (short novel or short story collection), poetry, and poetry in translation. Going forward, we will alternate works in translation with creative nonfiction. We have guidelines, FAQs, style sheet, and more updated information here. But the best way to decide if your manuscript might be selected and published by WWPH is to read our current books. See below for news on three of our most recent award-winning titles.

Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents/editors

Washington Writers’ Publishing House

WWPH WRITES Poetry

Karla Daly lives, writes, and edits in Washington, D.C. Her poems appear in SWWIM, Rust + Moth, Unbroken Journal, MER: Mom Egg Review, and elsewhere. She is a recipient of DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities fellowships and a midlife graduate of American University’s MFA Creative Writing program.

THE KEY

How can I express these compound griefs?

At my father’s viewing, I told an old friend,

I feel like I have no self.

What I meant was, like I have no will.

Like I have no body. Like my hungers

are secondary, tertiary, quaternary.

Like I’m a robot, an automaton.

Like I’m a broom.

She held my eyes hard and mouthed, I know.

Pressed a tarnished key into my hand. Ah,

she, too, had swept and swept.

©Karla Daly 2025

WWPH WRITES Creative Nonfiction

CRIME SPREE AT THE IGA

It’s fall, first year of high school, late 1960’s. Salem, Oregon.

I should be running cross country this year, given I was somewhat of a track star in 9th grade, taking first place in a city-wide meet in the three-quarter mile. But instead, I decide to take an after-school job as a stock boy at the local IGA grocery store in north Salem. Our family is by no means poor, but Dad never lets up griping about prices and the economy, and I figure it’s a way to gain favor with him by showing I’m able to join the workforce and hold a job. I’m in constant competition with my two older brothers for Dad’s approval.

The stock boy spends a lot of time putting cans on the shelves in an orderly fashion and helping customers with carrying their groceries out to their cars. I work with a senior stock boy, Frank, who shows me the ropes. And he teaches me how to steal. Not that he gives me any formal lessons; I just happen to observe him one night. I don’t mention I saw him, but he must know I did.

I’m into my Rebel Without a Cause phase. Up till then, I’ve only indulged in petty stuff like shoplifting crime paperbacks and an occasional Coke. Frank shows it’s deceptively easy to boost beer out of the storeroom. Just pull a car along the side entrance at night and load cases of beer into the trunk.

The first time I try it, after contemplating the brazen act for a few days, it’s pretty scary: the risk of getting caught, jail, Dad’s wrath. I wait until it’s close to closing time, when traffic in the store will be low. The sliding doors to the coolers in the back are unlocked. There’s the thrill of committing a felony and getting away with it. Precious, lovely cases of Olde English, Bud, Schlitz, Miller – the champagne of bottled beer. Over a few months, I heist twenty cases, all perpetrated in the creepy shadowland of a deserted stockroom. I hide the beer in the family attic above the garage, where you have to pull on a string to bring down the folding ladder and heave the cases up to a waiting wooden trunk. I share the beer with my small circle of pals, overindulging in parked cars at Bush Pasture Park. Olde English Ale tends to be especially vomit-inducing.

Shamefully, when Dad finally gets suspicious and discovers all the beer up in the attic, I lie and tell him I’ve been holding it for my friend Ron Petsch, who is the real thief. An early kink in my soul. Ron was the first high school friend with whom my buddy Curtis Reid and I got drunk on a Friday night while watching horror films at his house.

+

Four years later, I’m a college sophomore. I start feeling guilty about what I’d done. Maybe I’d been a jerk. Maybe my actions hurt other people, something I thought I was too cool to consider before. After much self-reflection, I asked myself,—Should I? Does it matter? Any chance I’ll get into trouble?

I return to the store and ask for a private meeting with the store manager in his office. Expressionless, he invites me back to his spartan cubbyhole. I lay it all out, the details of my late-night heinous crime spree on his premises, offering to make good on his loss. He’s a cold fish, like he’s been spending too much time in the produce department. Without saying a word, he sits down at his desk with his calculator and adds up the costs, plus interest. As I recall, the total is around $75 dollars, equal to $700 in today’s dollars. I write him a check. There’s none of the heartwarming reaction I had anticipated—how he would congratulate me on the tough decision to come forward, how it was surely a character-building decision on my part, that I’ve helped restore his faith in humanity. Nothing. He just takes the check, avoiding eye contact, and waits quietly for me to leave.

Walking out, I don’t feel any of the positive emotions I had anticipated: how, after finally taking responsibility for my crimes, load off my shoulders, I could now look forward to a good, clean life of hard work and well-earned rewards. I had deluded myself. His reaction only serves to deflate my faith in humanity, in that he had no real human reaction to my gesture. Now, I only regret my decision to return to the scene of the crime, the IGA, and come clean like a boy scout. I could have used that money. The bastard.

Paul Grussendorf is a graduate of Howard University Law School. He is an attorney representing refugees and asylum seekers and a former immigration judge. He is a consultant to the UN Refugee Agency. His book, My Trials: Inside America’s Deportation Factories, is a scathing indictment of America’s dysfunctional immigration system.

©Paul Grussendorf 2025

WWPH NEWS

We celebrate Black History month with our award-winning authors…all their books are available everywhere books are sold. Support your WWPH and purchase them here at bookshop.org. Here’s the link.

Our Award-Winning Books Are Receiving RAVE Reviews…

Megan Doney, along with Bernardine ‘Dine’ Watson, author of Transplant: A Memoir (WWPH, 2023 Nonfiction Prize-winner), will be guests at the Brown Bag Lunch series on March 20th at 12 noon, ET discussing HOW TO WRITE AND PUBLISH YOUR MEMOIR. Join us on Zoom with your brown bag lunch! Free and open to all. Please register here.

Read the entire DC Trending review here...and read FOR THE BLESSINGS OF JUPITER AND VENUS, by Varun Gauri, winner of our 2024 Carol Trawick Fiction Award. Available everywhere, books and ebooks are sold, including at our bookshop.org affiliate page here.

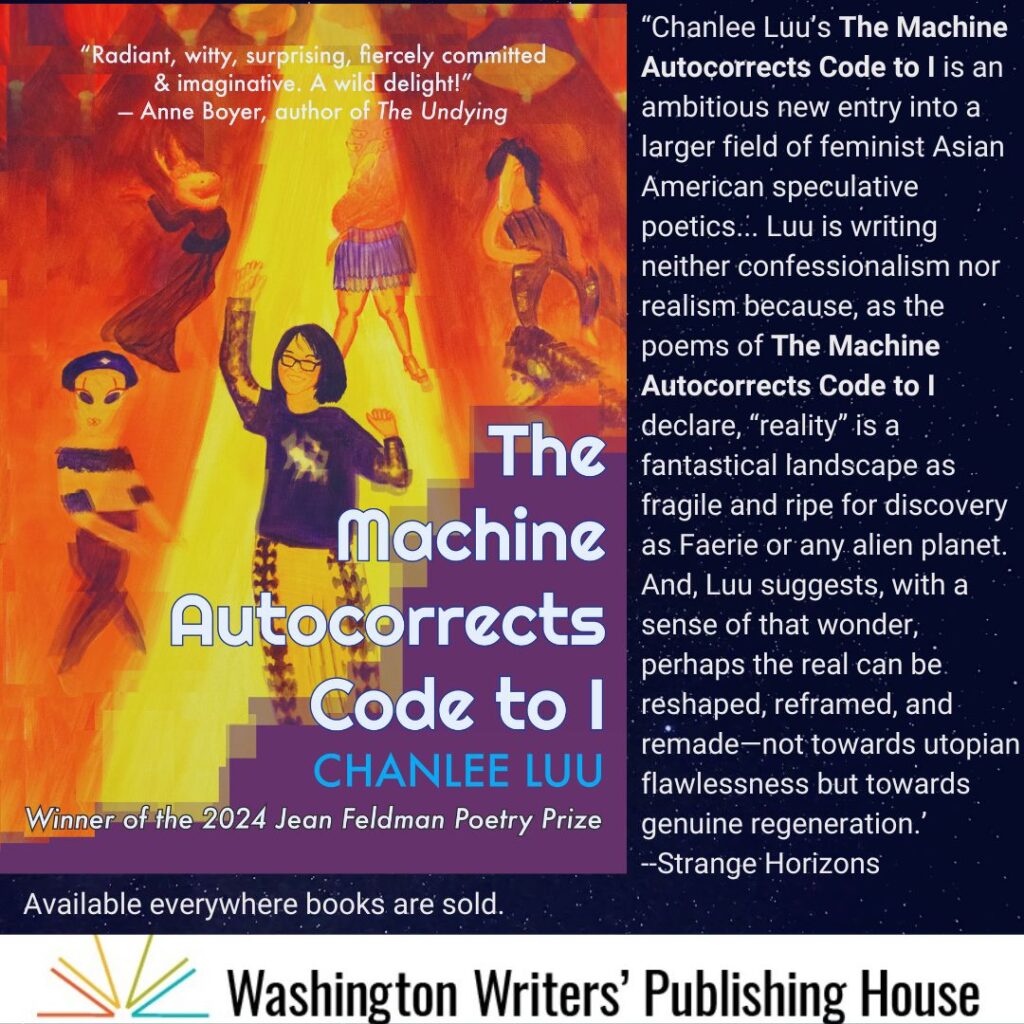

Read the entire Strange Horizons review here… and read The Machine Autocorrects Code to I by Chanlee Luu, winner of our 2024 Jean Feldman Poetry Prize. Available everywhere, books , including at our bookshop.org affiliate page here.

INSIDER NEWS… if you are considering submitting to WWPH, check out our guidelines and FAQs (new for 2025!) here.

WWPH WRITES is open for submissions! We now pay $25.00 for poetry (up to 3 poems) and prose (up to 1,000 words of fiction or creative nonfiction). Free to submit! More details at our Submittable page here.

Thank you for being part of the Washington Writers’ Publishing House community!